It’s a Friday afternoon in early April, two days into my Belgian beer holiday. As I write this I’m sitting in the modern tasting room of Brouwerij Drie Fonteinen, savoring a 2012 vintage bottle of oud geuze and a cheese board. Sunlight streams through the windows, it seems like the first completely sunny day in weeks. A modern windmill twirls lazily in the distance, time seems to slow down. I’m the only customer, which lends a tranquil, contemplative feel to the moment. Thoughts of the tour I took earlier that day at Cantillon are still running through my mind, while the glasses of lambic I had after the tour are running through my body. This is one of those moments where everything seems perfect.

I’ve come to Brussels to learn more about lambic, the world’s most romanticized beer style. Just about every aspect of brewing a lambic falls somewhere on a spectrum that runs from quirky to wildly impractical. The grains are a blend of malted barley and unmalted wheat. The hops are aged for years to minimize their aroma and flavor contributions while retaining their antimicrobial properties. Instead of pitching commercial yeast the wort is left exposed to ambient air so that wild airborne yeast and bacteria can take up residence. The fermentation occurs in oak barrels, each containing its own colony of yeast and bacteria, rather than stainless steel tanks. Finally, the beer from various barrels is blended in proportions determined by the master blender to obtain a final product that has some modicum of consistency from batch to batch. You would be hard pressed to make up a less efficient, more unpredictable way to make beer if you tried.

Like champagne, lambic beer is an appellation. Only those breweries who use traditional methods and brew in the valley of the river Senne near Brussels can call their beer lambic. At the turn of the 20th century there were hundreds of lambic producers in this region, but only a dozen or so remain. Only one, the world famous Cantillon, is actually located in Brussels.

Cantillon

Given the importance of beer in Belgian culture, I naively thought Brussels, a city of over 1 million people, would be chock full of breweries. I was surprised to learn that it is only home to a half-dozen breweries, and only two— Brasserie de la Senne and Cantillon—are more than a few years old. I’m a big fan of Brasserie de la Senne, and if you come to Brussels I highly recommend you try a Taras Boulba, Jambe de Bois, or one of their other offerings [1]. They are one of the most underrated breweries in Belgium, but no match Cantillon in terms of history and character. Cantillon manages to simultaneously be a museum for an old-fashioned way of brewing that almost died out, and a magnet for beer geeks from all over the world.

You can visit Cantillon anytime during business hours and do a self-guided tour, but guided tours are only given on Friday and Saturday mornings (check the Cantillon website for details). I’ve booked a spot on a Friday tour that starts at 11:15 am. As I make my way from our rented flat near Mont de Arts, I pass through the impressive and ornate Grand Place that contains the Belgian Brewers Museum (impressive facade, underwhelming content), past the surprisingly small Manneken Pis statue that is easily obscured by groups of photo-snapping tourists. I continue to work my way southeast, away from the city center. Eventually the restaurants, chocolate shops and beer stores selling €15 bottles of Westy XII give way to a more mixed residential neighborhood. Some people say that Cantillon is in a sketchy part of town. I think that description is a bit exaggerated, but you do see more immigrants, more middle eastern restaurants and mosques, and definitely no cherry orchards or open fields. The white washed brick building that houses Brasserie Cantillon is flanked on either side by industrial buildings that have been converted to community churchs.

My companions on the tour come from all over the world. People from Romania and Italy, from Germany and Japan, from the UK, Ireland and Canada, but the largest contingent is from the United States. The tour lasts about 90 minutes and costs €9.50, which includes two complimentary glasses of beer at the end. Cantillon only brews from mid-October until sometime around the end of March, because the levels of airborne bacteria become too high during the summer months [2]. I’ve arrived a week or so after the end of brewing season, so all the equipment has been cleaned for the summer break.

Cantillon was founded in 1900, with equipment that was already several decades old by that time. Due to the historic character of the brewery they bill themselves not only as a working brewery, but as the Brussels Museum of the Gueuze [3]. The only breweries I’ve visited that bear a resemblance to Cantillon are Theakstons and Hook Norton, rare surviving examples of Victorian tower breweries. Like those English breweries, Cantillon adopts a vertically-structured design, with each stage of the brewing process taking place on a different floor. Unlike Theakstons, which has the mash kettle on the top floor and the fermenters on the ground floor, the layout at Cantillon is inverted, finishing with the all-important coolship in the attic.

Our first stop is the mash tun, a metal vessel with wooden slats on the outside and the most intriguing steam punk, multi-pronged mixing apparatus on the inside. Cantillon uses a grist bill is 65% barley/35% unmalted wheat, and brews a single batch per day, 2 to 3 times per week. The mashing stage lasts an unusually long three hours finishing at a temperature of 72 °F. Lambic brewers use a so-called turbid mash, which involves a relatively thick mash and several steps of removing a portion of liquid from mash, boiling it, and then reintroducing it to raise the temperature (see the Milk the Funk wiki for details). The goal of turbid mashing is to break down proteins while creating a relatively high proportion of complex sugars (a dextrinous wort) that wild yeast and bacteria slowly break down over time.

Once mashing is finished, the wort is pumped up one floor for the boil. Once again Cantillon stretches this step out for much longer than your typical brewery. We were told the boil lasts anywhere from 3-5 hours, during which time the volume is reduced from 10,000 L (100 hectoliters or 85 US barrels) to about 7,500 L. At this stage hops are added as they would be for any style of beer. However, at Cantillon the hops are aged for three years to minimize their aroma, taste and bittering contributions. We were told that Cantillon normally use Saaz hops, but given how they are treated any low alpha-acid hop should do the trick.

Next, we make our way up to the attic where the gleaming copper coolship resides. Once the boil is finished the wort is pumped up here to cool and interact with the outside air, leading to the all-important spontaneous fermentation. On a brew day the coolship would typically be filled in the late afternoon, a process that takes over an hour. The wort is then left in the coolship to cool overnight. The optimal range of night time temperatures for brewing lambics ranges from −4 to 8 °C (25 to 46 °F), which is why brewing ceases in the summer months. I’ve always heard that spiderwebs are sacrosanct in a lambic brewery, because the spiders eat the fruit flies that are drawn to spilled beer. While I did see spiderwebs in the barrel storage area, on today’s visit a brewer is cleaning the cobwebs from the wooden rafters of the attic. Apparently even the lambic brewers clean house from time to time.

The next step is to transfer the now cool and inoculated wort to oak barrels repurposed from the wine and spirits industry, where over the course of years it will be turned into the elegant, funky, sour end-product that is lambic. Much of the space at Cantillon is devoted to storage of the barrels stacked in long rows three barrels high. Our guide tells us that the barrels are typically used 6 or 7 times before being replaced. Different barrels age beer for varying lengths of time. The best known lambic style, gueuze, is a blend of beer from barrels that have aged 1, 2 and 3 years.

The tour concludes in the tasting room, which doubles as the reception area for the brewery/museum. The tasting room consists of wooden chairs distributed around a handful of retired barrels and a few small wooden tables. There is a pot belly stove in the middle of the tasting area. It’s not fired up today but presumably it gets a lot of use in the winter. There is a modest bar to the left of the tasting area. Today they are serving unblended lambic, gueuze, kriek, and Rose de Gambrinus (lambic with raspberries).

All of us start with a complimentary pour of the unblended lambic that has been barrel-aged for one and a half years. The beer, which is poured straight from a ceramic jug, is golden and hazy to the point of being opaque, perfectly still with no head to speak of. The nose has that complex, balsamic note that comes from a blend of various carboxylic acids, including lactic and acetic acids. The taste is sour as you would expect, but not over the top. The presence of various esters adds fruity flavors that tend toward green apples and lemon peel. The mouthfeel has considerably more viscosity that you might expect from a low abv wheat beer, no doubt this comes from the formation of strong hydrogen bonds between carboxylic acid molecules and water [4].

Next, I move onto the gueuze, which is a blend of 1, 2 and 3 year-old lambic. The appearance is similar to the unblended lambic, but now there is some effervescence that comes from bottle fermentation of the young beer used in the blend. This not only adds a bit of white head, it boosts the complex balsamic, fruity aromas. Tastewise it’s similar to the unblended lambic, but the carbonation lightens the mouthfeel and subtly improves the drinking experience in my opinion.

At this point I’ve used up the tasting tokens that come with the tour, but that doesn’t mean I’m finished. I purchase a glass of the kriek, which is made by adding sour cherries to lambic that has already been aged for approximately 2 years. The beer is then aged on the fruit for an additional 2–5 months. Once the yeast and bacteria have had their way with the cherries there is no residual sweetness left behind, unlike the sweetened lambics that are more prevalent in the market. Nevertheless, the presence of cherry flavors, and just a hint of an almond-like nutty note from the pits, makes the sour character less overt, and a bit less funky to my palate.

Given how difficult it is to track down Cantillon bottles outside of Brussels (I’ve yet to come across a bottle of Cantillon on the shelves of a US store) you can’t leave without picking up some bottles to go. Were it not for the limitations of transporting beer on an airplane, I’d happily buy a case of beer. As it is I settle for a variety pack that contains one 375 mL bottle each of the gueuze, the kriek, and the Rose de Gambrinus (for €15). I also purchase a 750 mL bottle of the Grand Cru Bruocsella (€9.50) that is made exclusively from three-year lambic.

Drie Fonteinen

You’d think visiting Cantillon would check the box on lambics, but just to be thorough I make the journey out to Brouwerij Drie Fonteinen (Three Fountains Brewery) upon leaving Cantillon. It’s a 10 minute walk to the Brussels-South train station where I hop on a southbound train. Three stops later I get off in the small town of Lot and make an even shorter walk to Lambic-O-Droom, Drie Fonteinen’s new tasting room and barrel aging facility. The setting is distinctly different from Cantillon. Here there are trees and grass, and the sound of birds chirping in the distance. At one point I cross a small river without thinking too much about it, but when I look at the map on my phone I realize it’s the Senne.

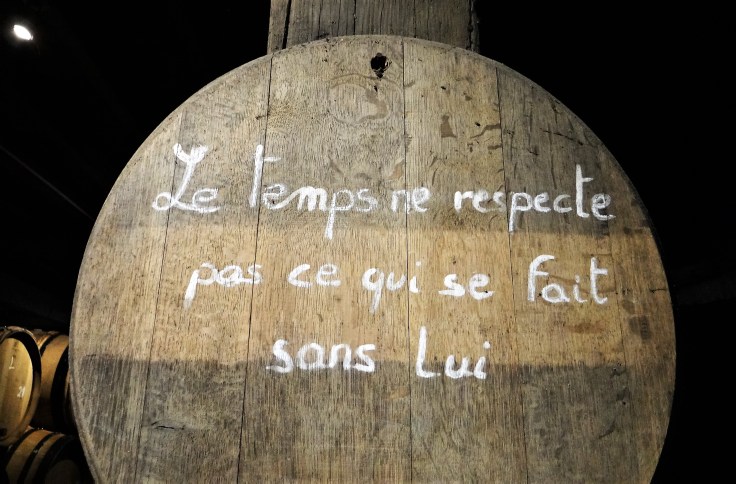

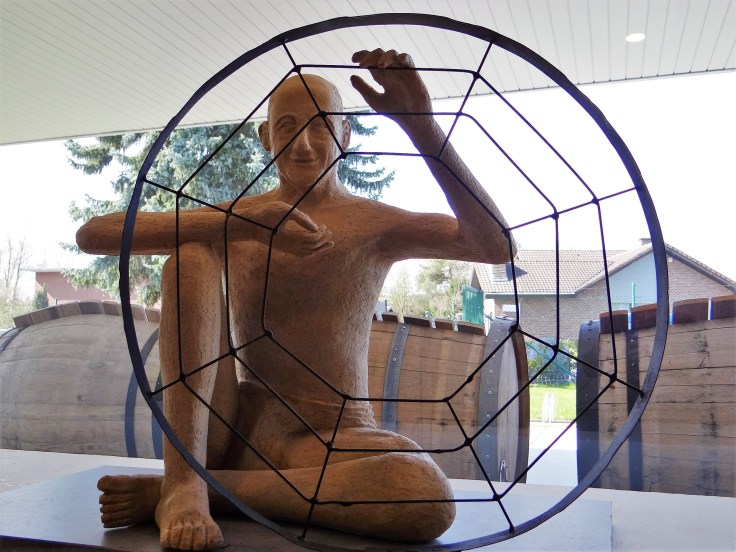

The Drie Fonteinen tasting center couldn’t be more different from Cantillon. The facility, housed in a long one-story building that was previously a warehouse, made it’s debut in the fall of 2016, and is open to the public Wed-Sat from 10 am to 5 pm. There’s a row of picnic tables in front of the building and three (presumably retired) foeders on display to the left of the building. If you go around to the backside you will find a small orchard of schaarbeekse cherry trees. Inside the tasting room is modern, elegant, and rather quiet. The room is filled with a half-dozen large tables made from the tops of old foeders. Natural light streams into the room, aided by dozens upon dozens of lights hang from the ceiling, each ensconced in the upper half of a dark green beer bottle. Various bottles for purchase sit on shelves mounted on the back wall. The back wall also contains a window that looks in on the space where barrel aging, blending and bottling take place.

Tours are given on Saturdays at 10:30 am for individuals, and by reservation for larger groups. Unfortunately, I’ve not timed my visit well enough to manage a tour. For those who are curious there’s a nice description of the process, full of many pictures on the Belgian Beer Specialist website. The tldr version is as follows. Wort is brewed in nearby Beersel, using a process similar to Cantillon, but with modern equipment or purchased from other Iambic brewers. Interestingly, Drie Fonteinen uses a four-pan, double-decker coolship. After inoculation in the coolship, the wort (roughly 3000 L) is transferred to a large plastic container and transported 4 km to the barrel aging facility here in Lot. In other instances Drie Fonteinen gets their wort from other Lambic brewers, such as Boon or Lindemans. Whereas, Cantillon age their beer almost exclusively in barrels, Drie Fonteinen uses a mixture of foeders and barrels.

Aside from a few selections (lager, blonde) geared toward lambiphobes who might find themselves here with a friend or a group, the beer menu is made up entirely of Drie Fonteinen lambics, mostly in either 375 or 750 mL bottles. Selections of the oude geuze range from a 375 mL bottle of the 2017 vintage for €6, to a 750 mL bottle of the 2004 vintage that will set you back €120. There are also a few fruited lambics, including the oude kriek and intense red. You can also get 1.5 year old unblended lambic as you can at Cantillon, geuze that has been blended and is waiting to be bottled, and faro, a traditional style made by mixing unblended lambic from a hand pump with candy sugar.

Like a kid in the candy store it’s hard to choose, but I eventually opt for a 375 mL bottle of oude geuze from November 2012 (€15), and a cheese board. The beer comes in a cork and cage dark green bottle, whose makeshift label was partially removed some time ago. The beer is deep golden, translucent rather than opaque. The nose has that complex sour, fruity aroma. The taste is notable for its complex phenolic spiciness. It’s hard to put into words but compared with the Cantillon gueuze the tart acidic notes seem more deeply integrated with the malts and there is a bit less barnyard funk. Of course, it’s not fair to compare a beer that was bottled nearly six years ago with the more recent vintage I had at Cantillon, but to my palate the 2012 Drie Fonteinen Oude Geuze is a more refined beer. The cheese board, which comes with a hunk of freshly baked bread and two spreads (a fruit jam and a brown mustard), is the perfect compliment to the beer. It doesn’t get much better than this, and since the story has now come full circle this seems like the perfect place to leave it.

Closing Thoughts

If you are lucky enough to visit Brussels I strongly recommend that you visit both Cantillon and Drie Fonteinen. They are very different experiences, each wonderful in its own right. While you are at it, you might as well throw in a visit to one of the bars or cafés in the city that serve lambics. Later that evening my wife and I checked out Moeder Lambic café, a modern beer bar that serves 5-6 lambics alongside a good selection of other Belgian and craft beers. On our visit I had a glass of Tilquin Gueuze to broaden my sampling experience, before heading off to the Delirium Café for their famous golden strong. Because of it’s scarcity Cantillon has become highly coveted in the US, but the other lambic producers that I sampled in Brussels are making beer that is comparable in quality to Cantillon, so don’t let availability discourage you from tracking down a bottle of oude gueuze for yourself. A vintage bottle of Drie Fonteinen is a treat to be savored, Boon Mariage Parfait is another excellent option.

If interested you can check out my other posts that document my Belgian beer odyssey.

- Belgium or Bust

- Hitting the Trappist Ale Trail Part 1 – La Trappe & Westmalle

- Hitting the Trappist Ale Trail Part 2 – Into Wallonia

- In Flander’s Fields – Visiting Rodenbach and Westvleteren

Footnotes

[1] Brasserie de la Senne is a production brewery that unfortunately isn’t set up for individual visits. However, according to their website if you can get at least 15 people together they will do group tours by appointment.

[2] I found this interesting quote from Cantillon owner and brewmaster Jean van Roy in a post on the Belgian Beer Specialist website, “One of the reasons why bacteria are more prevalent in warm weather is the presence of insects. Insects are an important trigger for bacteria being active, and … there are no insects active in the winter time.”

[3] Both spelling and pronunciation of the blended form of lambic can be confusing to English speakers. The French spelling is gueuze and is pronounced something along the lines of gerz, while the Flemish spelling is geuze and the g at the beginning of the word is deemphasized while the uh at the end is more pronounced, something like hherzuh.

[4] To experience a first hand observation of the viscosity of carboxylic acids go pour some vinegar into a narrow cylindrical glass and see how it flows and sticks to the walls of the glass.

Are you going to be at the BXL Beer Fest? Jean Van Roy and other legends will attend personally.

Unfortunately I don’t know when I will have another chance to get back to Belgium, but not this August for sure. It looks like a good festival though, I wish I could attend.

Well crafted write up – relived our visit to Cantillon through your words. Extraordinary place.

In a world with 10,000+ breweries it’s exceedingly hard to be unique, but I don’t it’s going too far out on a limb to use that term when describing Cantillon.

Outstanding. No words for how envious I am of your experience in Belgium!

I was lucky to have the chance to explore Belgium. Thanks for reading, and taking time to leave a comment.