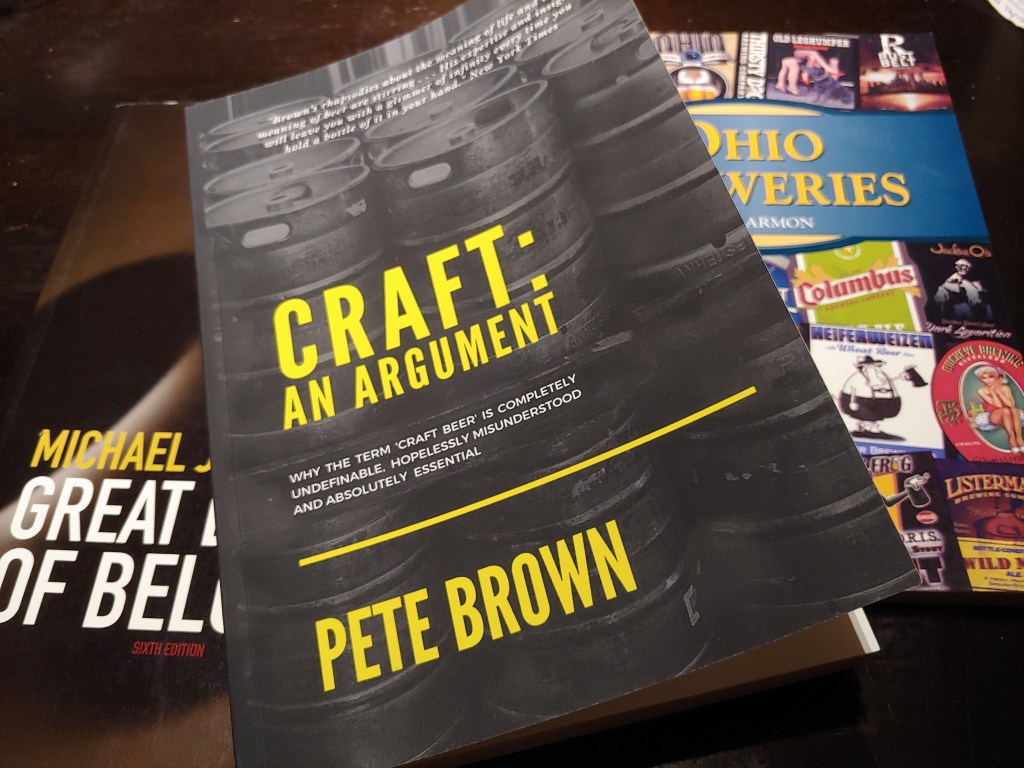

Recently a group of friends started a beer book club. The basic idea is to read books about beer, and then talk about those books while drinking beer, because after all there’s nothing like broadening your horizons. At least that’s how I assume the club will operate, because we’re still working on our first book, Pete Brown’s “Craft: An Argument.” A work that depending on your perspective is either a thought provoking 200 page read or a futile exercise in a defining a term that has little meaning. Apparently, the North American Guild of Beer Writers were leaning toward the former when they named it Best Beer Book of 2020.

As Brown points out early on in his book, after years of moving the goalposts on the meaning of craft beer, the Brewers Association have largely retreated from this debate, instead circling the wagons over the concept of independence. While much easier to quantify, defining the integrity of a business by the holdings of their owners is about as appealing as a pint of cellar temperature Busch Light from a gravity pour cask. Is Boston Beer Co., who now sell more cider, seltzer and hard tea than beer, really more craft than Anchor, just because the latter are now owned by Sapporo? Is Bells more craft than Founders, since Spain’s largest brewery (Mahou San Miguel) own 90% of Founders? What about Ballast Point who were independent craft brewers until 2015; then weren’t after being bought out by Constellation, and are now back in the club after being unloaded in 2019 (at a significant loss) to investors who also own the otherwise little-known Chicago area brewery Kings and Convicts? [1] I suppose one could make an argument in favor of those classifications, but in my personal opinion they ring hollow. On this point, Pete and I find common ground. The challenge is finding the right criteria to separate the wheat from the chaff.

In the first part of his book Brown asserts that it’s nearly impossible to define craft beer. He follows this up with a rather lengthy interlude on topics such as handcrafted furniture, wheelwrights, Paul Gascoine at the 1996 European Championships, and open plan offices. This middle part of the book is meant to put the meaning of the word craft (or cræft), as it exists outside of the world of beer, into context (except for the chapter on Sid Meier’s Civilization III which may be more a reflection of Pete’s quarantine pastimes than relevant in any meaningful way to the craft argument). This section of the book did help me understand why I get satisfaction out of homebrewing, cooking, gardening, and the like, but it didn’t help much with the ethics of visiting Wicked Weed’s Funkatorium.

Rather than spill the beans on how Brown resolves this conflict (you’ll just have to read it for yourself), I’m going to give you my take on the vocabulary we should be using for beer as we move into the third decade of the twenty-first century.

Let’s start with three central questions. Do we need a label to tell the difference between breweries that are worthy of our support and those that are not? If so, should we call the “good” breweries craft breweries, independent breweries, microbreweries, or something else altogether? Finally, what criteria should we use to decide who belongs in the club and who doesn’t?

I have a good friend who argues that craft beer is an unnecessary label, a term made up by grocery store managers to organize their shelves and guide the uneducated consumer. While I can understand his desire for a utopia where every beer stands on its own merit, it seems to me that most people who take beer seriously do not share his point of view. Here are a few points I would offer to bolster my argument:

- The brewery that my friend works for is a member of the Ohio Craft Brewers Association, as are nearly 400 other breweries in Ohio, but not the Budweiser brewery a few miles north of my house.

- It was not so long ago that the (US) Brewer’s Association ran a PR campaign aimed to get everyone to differentiate craft beer from crafty beer, lest someone confuse Allagash White (craft) and Blue Moon (crafty) as being similar beers.

- Along the same lines the BAs Independent logo seems to be widely used. While technically not the same thing as craft beer, it’s clearly an attempt to differentiate some breweries from others.

- When I lived in the UK (where the classifications for beer are if anything more confusing than in the USA) just about everyone (but me) seemed to agree that craft beer and real ale (aka cask ale) were different. I even wrote a blog post about that topic.

I think for the most part both drinkers and brewers of “craft beer” want to have some way of setting themselves apart from the international conglomerates of the beer world. Except for BrewDog who seems to be trying as hard as they can to become an international conglomerate, but even BrewDog (especially BrewDog?) want to be seen as craft beer.

If you are still reading, hopefully I’ve convinced you that many people want the vocabulary to divide the world of beer into those who are worthy and those who are not. What’s wrong with the term craft beer you may ask? Sometimes, the literal meaning of a word is appropriate for what you want to describe, but its use can still be confusing. Football would seem like a logical name for a game that involves moving a ball almost entirely with your feet, but if I use it without some qualifications here in Ohio confusion is likely to ensue. I would argue the term “craft beer” suffers from the same fate. Even though it wasn’t used until 1984 the term craft beer is strongly associated with the rebirth of interesting, flavorful beer in the United States some 40 years ago. [2] While this label is widely used for breweries located outside the US, it’s less clear that it applies to breweries that predate the likes of Anchor and Sierra Nevada? Can a brewery that is nearly a century old and only makes one beer, like Orval, be a craft brewery? What about a brewery that is nearly a millennium old, like Weihenstephan? If I judge by what’s in the glass, there’s no question that these breweries should be discussed in the same genre as craft beer. On the other hand, independent breweries would be a questionable label, given that Orval is owned by the church and Weihenstephan by the state.

I can already hear some of you out there grumbling. “Mr. Pat’s Pints is trying to categorize the likes of Orval and Weihenstephan as craft beer. I can’t wait to hear what’s next? Is he going to claim that Viking Metal and Folk Metal are the same thing?” While I’m purposefully trying to be provocative, there are limits. Just because they both incorporate traditional instruments and guttural, incomprehensible vocals doesn’t mean you can’t lump them together in the same category. Anyone with a Subway for Sally album can tell you that.

Coming back to beer, let’s not waver from our quest to find a term that applies not only to Land Grant, Fat Heads and Little Fish, but also to Theakstons, Rodenbach and Pilsner Urquell. While I think “craft” is a perfectly appropriate term for a brewery that cask conditions their beer, or ages it for years in giant oak foeders, or employs triple decoction mashing, it seems the term has become too closely linked to American breweries of recent vintage to be widely accepted.

Of course, what you call something depends on how you define that thing. [3] So, let’s start with the definitions and then work up to the name. I suggest that breweries who meet the following four criteria are worthy of your support no matter how old they are, their country of origin, or (to some extent) who owns them:

- Quality – A brewery that makes beers that are generally of a high quality.

- Identity – A brewery that has a distinct identity.

- Ethical – A brewery that follows ethical business practices.

- Transparent – A brewery that doesn’t try to obfuscate or deceive its customers.

If we take the first letters of each criterion (obviously granting me some license with the letter q) we arrive at a new term, quiet beer. It’s not exactly a marketer’s dream, nor is it likely to catch on with the young crowd, but you could do worse. As far as commercial products go beer is for the most part a quiet product. On a BJCP scoresheet, you evaluate appearance, mouthfeel, taste, and aroma, but there’s no points given for sound. Even a firkin of real ale, which contains live yeast, wouldn’t get you kicked out of a library. At a minimum I’d think the monastic breweries, like Orval and Chimay, could get behind this.

I’m sure you’re already planning on meeting some friends at the closest quiet beer bar or maybe a quiet beer taproom to celebrate this breakthrough in language, but if any sceptics remain let me briefly expand on each of the criteria.

Quality – The first and most important criterion for being counted among the breweries worth supporting is the quality of the product they produce. This is also the only criterion that is common to both my list and Pete’s. In earlier attempts to define craft beer the Brewer’s Association focused on the quality of the ingredients [4], and rightfully so, but the skill of the brewer is equally important. Big breweries have been guilty over and over again of cutting corners on ingredients to save money or make their beer taste bland in pursuit of a wider market share, but that’s not always the case. When SAB/Miller owned Pilsner Urquell and built a new brewhouse they retained the triple decoction mashing regimen that is traditional for that beer, even though many reputable German breweries have abandoned decoction mashing altogether. Small breweries are much less likely to do this, but more likely to make a beer that falls short because of errors in process or simply because the recipe was not well thought through. The current trend toward an endless string of one-off beers is not helping in this regard.

Identity – According to statistics on the Brewer’s Association website, there were 8,884 breweries in the US at the end of 2020, and a whopping 8764 of them were classified as craft breweries. Having imbibed my first beer in 1981 when there were less than 50 breweries in the US, I’m appreciative of the myriad of choice that we enjoy today, but I would contend that if that if this number were reduced, say cut in half, it wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing. The question is how would you do the culling? Obviously, the quality of the product would be tantamount (see criterion 1). Beyond that I would argue that the identity of a brewery, the intangible qualities that make it stand out from the crowd, are the next most important criterion. Guinness and Pilsner Urquell may not fall under the umbrella of craft beer, but they both make an excellent product that is immediately recognizable. They each pioneered a much-copied style of beer, and if for no other reason than for the sake of history I want those breweries to prosper.

While we might be able to agree that Miller High Life, Budweiser and PBR would be hard to distinguish without the labels, the same thing can be said for a lineup of hazy IPAs with various fruit puree additions. I’m all for neighborhood breweries that act in a similar role as the British pub, but if you are going to put your beer into a package and distribute it, I would advise breweries to pick a lane and perfect their recipes and techniques before branching out. Beers from Little Fish, Rockmill, and Pretentious can often be found in my refrigerator because I know these are local breweries who focus on perfecting styles that I enjoy. If I’m going to get in my car for an afternoon drive I’m more likely to head for Woolly Pig, Branch and Bone, or Hoof Hearted because they offer beer and/or an atmosphere that is not replicated closer to home. That’s not to say Rockmill shouldn’t make an IPA or Zaftig a kölsch, but at least perfect one category of beer before branching out in another direction.

Ethical – With so much choice at our fingertips there’s no reason to buy beer from breweries, large or small, who engage in questionable business practices or who are simply run by people with dubious morals. Who doesn’t want to support breweries that partner with community organizations, use local ingredients, try to do what they can to be sustainable with their use of energy and water? At a minimum pay your employees a decent living wage, treat your customers with respect, and avoid sexist, racist or xenophobic themes in your branding. Obvious non-starters for most of us would include sexual harassment or sexual assault, and racist hiring practices. With nearly 9000 breweries unfortunately it’s not too hard to find breweries that fail on this count, but in my experience there are a lot of good people in the industry as well. Finally, in my book it’s not OK to adopt practices that purposefully undermine other breweries and on this count the big boys like AB InBev have a pretty dubious record.

Transparent – The Brewer’s Association has been calling for greater transparency when it comes to ownership for some time now. I think that’s fair, after all if we are going to evaluate a brewery on their ethics we need to know who owns the brewery. It could equally well apply to ingredients, or process, or where a beer was manufactured. Some beers historically have a strong connection to a location, so when Newcastle Brown is brewed in the Netherlands or Goose Island 312 Urban Wheat is brewed in New York, I think the brewery should tell me this on the label. I’d like to know if the raspberry character of a kettle sour comes from additions of fresh fruit, aseptic puree, or artificial flavors and colors. Ohio breweries like Land Grant and Great Lakes have been out in front of this for a while, listing the malts, hops and other ingredients used in all their beers. Kudos to them and I’d encourage other breweries to follow suit.

I better wrap it up, but when you find yourself at an Extreme Quiet Beer Festival in the years to come don’t forget you read it here first.

Endnotes

[1] Kings and Convicts/Ballast Point is listed as number 30 on the Brewer’s Association list of the 50 largest craft brewers in the US.

[2] Quoting from Craft: An Argument, the first mention of “craft beer” was by beer writer Vince Cottone in a 1984 article published in the September-October issue of The New Brewer Magazine.

[3] Some people might argue it’s unfortunate to use the term World Series for a competition that is only open to teams from two countries.

[4] Until 2014 one criterion for membership in the Brewer’s Association (and thus the craft beer club) was the use of traditional ingredients. This was spelled out as follows: A brewer who has either an all-malt flagship (the beer which represents the greatest volume among that brewer’s brands) or has at least 50% of its volume in either all-malt beers or in beers which use adjuncts to enhance rather than lighten flavor. It’s not clear if this was dropped because of a shift to more adjunct grains like oats and wheat or because no one could remember what a flagship beer was.

Interesting, but an impossible dilemma. Having toured the local AB plant with the plant manager and the brewmaster, I would argue that they excel in terms of the “green” aspects of brewing.

Thanks as always for this piece of insight. It’s good to know that AB is doing what they can to follow sustainable practices in their operation. Especially when you consider the volume they produce. Out of curiosity what sort of things have they incorporated into their operations that stick out to you?